The Outsized Impact of Text Messages on Litigation

-

Published on Jun 8, 2023

By: Phil Favro, Principal, PRESA Consulting

Text messages are having an outsized impact on the results of litigation. To be sure, text messages may be highly relevant in certain cases, particularly since they often reflect unguarded communications from message participants on key issues. More often than not, however, the impact of text messages on litigation arises from a party’s failure to preserve such evidence. And the failure to preserve relevant text messages frequently occurs because neither the parties nor their counsel are aware of how the automated message retention and destruction features and functionality of these applications may impact preservation duties.

With text message deletion giving rise to so many spoliation motions, it behooves judges to better understand how messaging applications generate, retain, and eliminate message content. While judges cannot be expected to stay current with every technological development affecting text message preservation, having a basic understanding of particular retention and deletion settings can help empower a judge to better address these issues when they are raised in litigation.

This article will consider some key technological features associated with messaging applications that may affect the preservation of relevant text messages of which judges should be aware. Those features include automated deletion functionality that systematizes the elimination of text messages and the ability to “unsend” messages which can retract and permanently wipe out message content.1

“Automated Deletion” Functionality

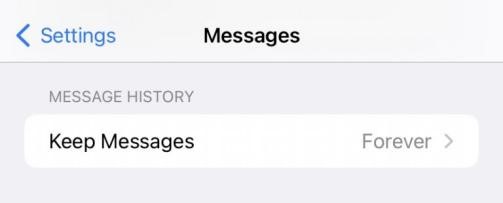

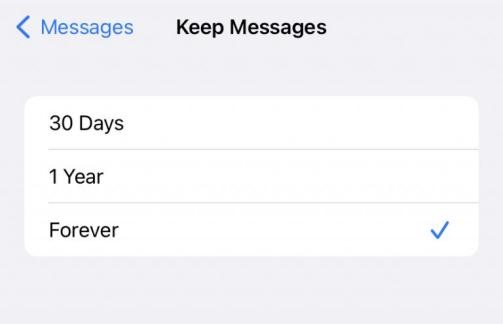

Apple provides an automated deletion feature that allows users to modify the retention of text messages (both iMessages and SMS messages) on iOS devices such as iPhones and iPads. While Apple’s factory default setting is “Forever,” users may change that setting to retain messages for only 30 days or one year, depending on which preference is selected (see figures 1 and 2, below). If a user enables the automated deletion feature for either time period, this may cause relevant information to be eliminated.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

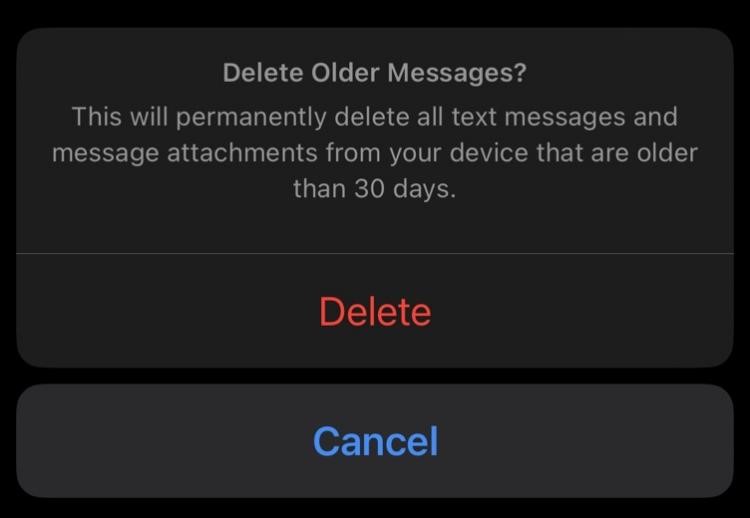

This is precisely what transpired in Hunters Capital, LLC v. City of Seattle, where the court imposed sanctions on the City of Seattle and several high ranking officials, including its mayor, for failing to preserve relevant text messages on their smartphones.2 Particular to the issue of automated deletion, the mayor deleted 5,746 messages after plaintiffs’ complaint was filed and the duty to preserve attached, with most of the messages being lost after the mayor enabled the 30-day automated deletion feature on her city-issued iPhone. It did not matter that the mayor disabled the automated deletion feature shortly afterwards and returned her phone to the factory-default setting of “Forever” message retention. Once enabled, automated deletion caused all of her messages older than 30 days to be permanently lost (see Figure 3, below).3

Fig. 3.

To remediate the harm from the mayor’s misconduct, the court issued a permissive adverse inference against her pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 37(e)(2), authorized plaintiffs to present evidence and argument to the jury regarding the spoliation, and awarded fees and costs against the mayor and other defendants.4

The automated deletion feature may cause additional mischief in litigation beyond merely eliminating text messages. Some parties have attempted to rely on this functionality as a way of exculpating their deletion of messages, asserting it was “only a mistake” that certain messages were systematically eliminated and therefore does not merit the imposition of severe sanctions under Rule 37(e)(2). In several of these cases, courts have found such an assertion cannot withstand scrutiny given other evidence suggesting the parties selectively eliminated text messages. Nuvasive, Inc. v. Absolute Medical, LLC is exemplary on this point.5

In Nuvasive, a defendant (Soufleris) argued that his text messages were eliminated as a result of his iPhone’s automated deletion feature. The court ultimately rejected this argument, finding instead that Soufleris had eliminated certain text messages during the six-month period leading up to the filing of the lawsuit. In doing so, the court contrasted message automated deletion functionality with Soufleris’s selective deletion of particular text messages: “[The] auto-delete function would delete all text messages prior to a certain date, not just messages within a timeframe crucial to the issues in this litigation.” The court held that Soufleris’s selective deletion of texts evinced an intent to deprive his adversary of relevant evidence and warranted the issuance of an adverse inference instruction to the jury.6

Hunters Capital and Nuvasive spotlight key preservation issues associated with the iPhone automated deletion feature of which judges should be aware. These cases also teach that judges who understand the functionality underlying automated deletion can make more informed decisions regarding related ESI spoliation issues.7 Beyond the realm of the automated deletion for iPhone text messages, judges also should obtain an understanding regarding the augmented automated deletion functionality with ephemeral messaging applications.8

“Unsend” Messages Feature

Certain messaging applications including Facebook Messenger and Apple’s iMessage (on devices using iOS 16, though not available for SMS messages) now offer users the ability to “unsend” messages. This “unsend” feature disables a recipient’s access to messages the user previously sent and may also allow users to permanently delete those messages. While marketed innocuously as a way to handle embarrassing mistakes,9 the Fast v. GoDaddy case10 is exemplary regarding the problems that Facebook Messenger’s “unsend” feature can present in litigation.11

In Fast, plaintiff used the “unsend” feature to prevent a former lay colleague (“Mudro”) from disclosing 109 relevant Facebook Messenger messages. Plaintiff’s action effectively blocked Mudro—who was helping plaintiff marshal evidence to support her discrimination claims—from producing the original, unaltered messages in response to a GoDaddy subpoena. Nevertheless, Mudro produced timestamps indicating the dates when she received the 109 “unsent” messages from plaintiff, the contents of which were replaced by the wording “this message has been unsent.” After GoDaddy filed its motion for sanctions against plaintiff, plaintiff finally produced 108 of the 109 “unsent” messages in their original, complete form just days before Mudro’s scheduled deposition, with one notable exception: Plaintiff permanently deleted a message memorializing an analysis she conducted with Mudro evaluating the strength of evidence supporting her claims.

The court in Fast concluded that the circumstances surrounding plaintiff’s elimination of this key message—i.e., the use of the “unsend” feature to prevent Mudro from disclosing the message’s contents and then plaintiff’s subsequent deletion of that message—warranted the issuance of an adverse inference instruction at trial (the court imposed additional sanctions to address plaintiff’s spoliation of other evidence). Shortly afterwards, plaintiff voluntarily dismissed her discrimination claims with prejudice, but not before paying $10,000 to GoDaddy in monetary sanctions. According to the court, the $10,000 sanction award was the price of dismissal given plaintiff’s widespread and brazen spoliation of Facebook Messenger messages and other relevant data.12

Fast emphasizes how parties can spoliate relevant evidence by “unsending” messages after a duty to preserve has attached. Though undoubtedly problematic, the “unsend” feature does leave behind a digital fingerprint, indicating the fact that a message was actually unsent (Facebook Messenger) or the date and time a message was unsent (iMessage). As Fast teaches, that information—left on the recipient’s devices—can be useful for tracking back the unsent messages to the party who sent the information.

Additional Messaging App Issues

In addition to automated deletion and the ability to “unsend” messages, other messaging application features that may affect preservation include the option to edit previously sent messages. Various applications—iMessage, Microsoft Teams, Slack, and LinkedIn, to name a few—offer users this ability. Like the “unsend” feature, this option seems innocent enough, ostensibly allowing a sender “the opportunity to fix a typo.”13 But while certain applications make the nature of the edited and original content apparent to both the sender and recipient (iMessage), other applications (LinkedIn, Teams, and Slack) only indicate that a message has been “edited,” leaving some recipients wondering exactly what the sender excised from the original message.

Beyond the technical features that render text messages particularly dynamic, judges should also be on the lookout for fraudulent text messages. While the issue of fabricated evidence has always been a possibility,14 the sophistication of technology and the savvy of users have increased the potential that proffered evidence may not be what the proponent claims.15 Indeed, recent cases have prominently highlighted the issue of fabricated text messages and the need for judges to vigorously guard against such abuses to the legal system.16

Conclusion

Judges should expect the technological features impacting text message preservation to continue to evolve. As they do, messaging applications will likely offer different options that may affect the preservation and deletion of text messages. To address the disputes in litigation resulting from such changes more effectively, judges should carefully examine the issues in play, explore the role (if any) of technology on the elimination of relevant text messages, and obtain where necessary unbiased expert views on the technologies in question.